In my previous post, Writing that Hooks Readers-Neuroscience Hack #1, I discussed how elements of change affect our brains as we read. As promised, I”m back with the next installment of this multi-part exploration of the neuroscience behind writing that grabs our attention and pulls us in.

If you’ve ever watched an Olympic sporting event like the floor routine in gymnastics, you might have seen shots of athletes preparing to compete. They stand to the side, eyes closed, twisting their bodies around in odd ways. You know what they’re doing. They’re envisioning their routine, imagining the jumps, the turns, the tucks. The term for it is pre-visualization, and there’s plenty of data in the field of neuroscience to show that it improves performance in the live competition. The same things happening to those athlete’s brains occur inside readers’ minds when they read. Provided, that is, an author uses a few key tricks when they write.

Brain Hack #2: “Monkey See, Monkey Do” is a Truer Statement Than You Think

In 1996, a team of Italian scientists inserted electric probes into the premotor cortices of monkeys. They tracked neuron (nerve cell) activation in the animal’s brains when they reached for a toy or grasped a piece of food or brought a cup of water to their mouth to drink. Each time a monkey did something, the scientists noted which neurons fired during each activity.

Interestingly, they discovered that when a scientist reached for a toy or grasped a piece of food, the neurons in a watching monkey’s brain would fire in the same way as if the animal were the one performing the actions. The lead scientist said, “…we realized that the pattern of neuron activity associated with the observed action was a true representation in the brain of the act itself, regardless of who was performing it.” (G, Rizzolatti, et al. “Mirrors in the Mind.” Scientific American, 2006. pp. 54–61. Print.)

What does that mean? From a neuroscience, it means our brains simulate what we observe others do and experience. In the book The Storytelling Animal, author Johnathan Gottschall suggested that this phenomenon offers us a “safe” way to learn new skills. It also lets us assess possible consequences of specific actions without endangering ourselves.

What does that mean? From a neuroscience, it means our brains simulate what we observe others do and experience. In the book The Storytelling Animal, author Johnathan Gottschall suggested that this phenomenon offers us a “safe” way to learn new skills. It also lets us assess possible consequences of specific actions without endangering ourselves.

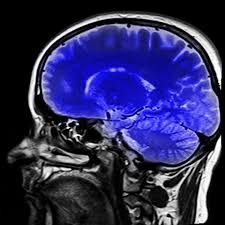

To better understand this idea, you have to know about a couple of specific types of neurons.

Motor Neurons

These are the nerve cells that stimulate our muscles when we kick, jump, or swing a bat. They originate in a region in our brain called the motor cortex and end in our muscles.

These are the nerve cells that stimulate our muscles when we kick, jump, or swing a bat. They originate in a region in our brain called the motor cortex and end in our muscles.

Mirror Neurons

These are the neurons our Italian scientist friends saw firing in their monkeys. The science is far from conclusive on why these cells exist. However, many folks believe mirror neurons help us understand the intent of other people’s actions. They also help us learn new skills by imitation.

These are the neurons our Italian scientist friends saw firing in their monkeys. The science is far from conclusive on why these cells exist. However, many folks believe mirror neurons help us understand the intent of other people’s actions. They also help us learn new skills by imitation.

Whereas motor neurons fire when we kick, jump or swing a bat, mirror neurons fire when we watch (or read) someone else kick, jump, or swing a bat. If a person is hooked up to a fMRI brain scanner while watching a film of an X-games freestyle skier launching off a half-pipe doing some crazy, twisty, flip thingy, the mirror neurons in their motor cortex light up brightly. Inside their brains, it looks like they’re the ones coming off the half-pipe. Even if they’ve never been skiing!

Writers Can Use Mirror Neurons to Deepen Reader Engagement

Include strong action verbs that reference specific body parts in your writing to stimulate your readers’ mirror neurons. The key to this brain hack working, however, is the specificity of your descriptions.

“He did a flip off the diving board.”

– this sentence uses an auxiliary verb (did) versus an action verb (flipped). Flip, in this sentence is a noun, a thing, not an action than can be mirrored in our minds.

“He flipped himself backward off the diving board.”

– in this sentence, flipped is an action verb, which is a stronger choice. Reading about an action, at least in theory, can stimulate mirror neurons. Also, we know something about the direction of the action (backward) and a rudimentary setting (the diving board). However, the verb flip refers to the whole body rather than specific body parts, so it doesn’t stimulate mirror neurons all that much.

“Pumping his arms like pistons, he heaved his weight downward against the edge of the diving board, then rode its recoil high into the air, tucking his knees tight to his chest as he spun, and craned his neck back as he sought to find the water.”

– I went a bit over-the-top with this one, but I wanted to make a clear point. This sentence contains multiple action verbs (pumping, heaved, rode, tucked, spun, craned, sought, and find). Many of the verbs reference specific parts of the body (arms, knees, and neck). The last element embedded into this sentence that is absent in the prior two examples is a clear goal. The individual is seeking the water. It’s the most engaging of the three because it does the best job of stimulating your motor cortex via mirror neuron activation.

So there you have it! Neuroscience hack #2: Mirror Neurons. Next time you sit down to write a scene, or edit a scene for that matter, pay attention to your use of verbs. Your readers will be pulled in and feel as if they’re living the story.

More posts about a neuroscience hacks writers can use to make their writing more engaging will be coming soon, so stay tuned.

Thanks for stopping by, and as always, happy writing to you!

These are the nerve cells that stimulate our muscles when we kick, jump, or swing a bat. They originate in a region in our brain called the

These are the nerve cells that stimulate our muscles when we kick, jump, or swing a bat. They originate in a region in our brain called the

It’s true! From an evolutionary standpoint, the brain is an organ with a singular purpose. To keep us alive. An essential part of “not dying” is noticing any kind of change to the current situation.

It’s true! From an evolutionary standpoint, the brain is an organ with a singular purpose. To keep us alive. An essential part of “not dying” is noticing any kind of change to the current situation.